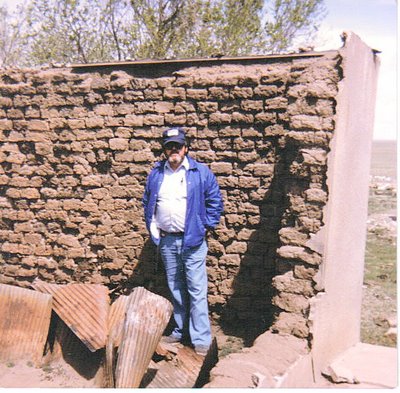

This is my Dad standing in the corner of the old ranch house where he was born.

One of the funnest things about visiting Grandpa and Grandma Kear in Clayton, New Mexico, was when us "boys" got to take the 27 mile road trip to the old farm. Grandpa would put the .22 rifle in the trunk of his 1960 Chevy and off we'd go, headed west.

That blue and white Chevy with the great "Batman" fins was the only car I ever knew my Grandpa Kear to own. He bought it used in the early 1960s and kept it until he died. He was a frugal man.

My grandparents moved to town in 1956 or 1957, my Dad's senior year in high school. The government had paid them to let their land, which had suffered erosion, go back to grass. They bought a house at 619 Oak Street and settled in. Grandpa worked as a mechanic and my grandma worked in the school cafeteria. Grandpa also owned a saw sharpening business.

Going out to the farm was incredibly fun for a young lad. Me, Grandpa Kear, Dad, perhaps Uncle Don and cousin Ricky or Uncle Dave and cousin Tony, would all pile out of the car and explore the old buildings, long abandoned. We'd get out the .22 and shoot at cans and bottles. There is something about the color of the sky and the scent of the wind out there on those Great Plains. There is a beauty that cannot be described with mere words. It must be felt. Looking to the west, you could see the Don Carlos Hills, looking north, the vague silhouette of Sierra Grande, one of the tallest lone peaks in the world. The native grasses waved silently in the ever-present breeze. A jackrabbit would start from behind a clump of brush and zig-zag off into the tan terrain. I was always told to "skin my eyes for an antelope," and many times I did see small herds of indigenous pronghorns.

On the farm there stood the remains of the house where my grandparents raised their four boys. It was an adobe house, built by loving hands and dried in the bright New Mexico sun. By the time I was able to know this house, it was but a shell. With the plaster mostly gone, the underlying adobe bricks were clearly visible.

My Dad was born in that house. On several occasions, he took us to the corner room where he was born on a summer day in 1938. There was almost a mystical connection between my Dad and that house, that land. It was as if his birth, his life, and that of his family, resonated within the very dirt that made up the adobe bricks of the house. There was a connection that could not be broken by the mere distance of time or space.

After Grandpa Kear died, the land was sold. My Dad made one last trip to the house, took an adobe brick from the wall of the room in which he was born, wrapped it in plastic, and kept it. The next time I drove down that lonely piece of highway, the house was gone.

After my Dad died, I kept that brick. You could almost feel a continuity between it and him. I hauled it all over with me. It always sat in my office, next to my desk. As all things do with time, however, that old brick began to disintegrate, it began to lose its form and fall into dust. A few years ago in the springtime I took that adobe brick from the wall of the house where my Dad was born and I placed it on his grave, where the Oklahoma rain could wash its dust into the hallowed ground where he sleeps awaiting the resurrection. It is only fitting that the dust that sheltered him at his birth should continue to shelter him in his death.